Abstract

A gray, fine-grained arkosic sandstone tablet bearing an inscription in ancient Hebrew from the First Temple Period contains a rich assemblage of particles accumulated in the covering patina that includes calcite, dolomite, quartz and feldspar grains, iron oxides, carbon ash particles, microorganisms, and gold globules (1–4 μm in diameter). There are two types of patina present: thin layers of a black to orange-brown, iron oxide-rich patina, a product of micro-biogenetical activity, as well as a light beige patina mainly composed of carbonates, quartz and feldspar grains. The patina covers the rock surfaces and inscription grooves post-dating the incised inscription as well as a fissure that runs across the stone and several of the engraved letters. Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) analyses of the carbon particles in the patina yields a calibrated radiocarbon age of 2340–2150 Cal BP and a conventional radiocarbon age of 2250 ± 40 years BP. The presence of microcolonial fungi and associated pitting indicates slow growth over many years. The occurrence of pure gold globules is evidence of melting (above 1000 °C) indicates a thermal event. This study supports the antiquity of the patina, which in turn, strengthens the contention that the inscription is authentic.

Keywords

- Jehoash Inscription;

- Archaeometric;

- Patina;

- Microcolonial fungi;

- Gold globules

1. Introduction

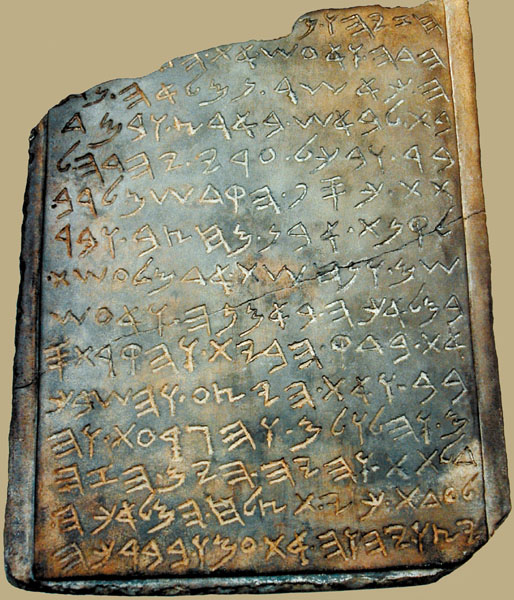

A rectangular dark stone tablet 31 × 25 × 9 cm in size was subjected to archaeometric examination by the authors. The stone tablet is engraved with an inscription in ancient Hebrew (

Fig. 1A and B) known as the “Jehoash Inscription” (JI). The inscription commemorates the renovation of the First Temple carried out by King Jehoash, who reigned at the end of the 9th century B.C.E. (

ca. 2800 years BP). A similar account of the Temple repairs is found in the Bible (Kings II: 12). This tablet represents the only Judahite royal inscription found to date. According to

Cohen (2005), the translation of the 16 lines of the ancient Hebrew is as follows:

“[I am Yeho'ash, son of A]hazyahu, k[ing over Ju]dah, and I executed the re[pai]rs. When men's hearts became replete with generosity in the (densely populated) land and in the (sparsely populated) steppe, and in all the cities of Judah, to donate money for the sacred contributions abundantly, in order to purchase quarry stone and juniper wood and Edomite copper/copper from (the city of) ‘Adam, (and) in order to perform the work faithfully (=without corruption), - (then) I renovated the breach(es) of the Temple and of the surrounding walls, and the storied structure, and the mesh-work, and the winding stairs, and the recesses, and the doors. May (this inscribed stone) become this day a witness that the work has succeeded (and) may God (thus) ordain His people with a blessing.”

The JI tablet is said to have been found near the southeastern corner of the wall of the Temple Mount complex, where it was used as a secondary building stone in a tomb. It was found in the Jerusalem antiquities market and it is now under the custody of the Israel Antiquity Authority (IAA). The authenticity of the Jehoash Inscription has been a fiercely debated topic over the past few years. Epigraphic and philologic analyses of the tablet are inconclusive as to its authenticity.

Cohen (2007) contended that if a forgery, it is a brilliant one, near genius.

Freedman (2004) advised not to rush to judgment; the Jehoash inscription may be authentic.

Sasson (2004) noted that the text of this inscription is not a forgery. If it is a forgery, then a combination of some incredible factors must have operated in producing it.

Cross (2003), however, maintained that the inscription is a poor forgery. This dispute should not come as a surprise, since no Hebrew royal inscription from the First Temple Period was ever found which could serve for typological comparison.

Ilani et al. (2002) and

Rosenfeld et al. (2005) concluded that it may be authentic based on chemical and petrographic analyses. Following their report on the patina to the IAA,

Goren et al. (2004) claimed that the inscription on the JI tablet was a forgery. New evidence based on microcolonial fungi (MCF) as producers of a black and orange-brown patina, strengthens the view that the inscription was not recently engraved.

2. Methods

The mineralogic composition of the tablet rock was determined by using a petrographic microscope and a Philips X-ray diffractometer. Samples were removed from the rock-tablet by using a diamond-tipped hand drill and from the patina by peeling with a sharp steel blade. A scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL-840), equipped with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS, Oxford–Link–Isis) was employed for detailed inspection of the physical properties and structural features of the tablet and its patina, as well as for chemical analysis. A Hitachi S-3200N SEM with low vacuum was used for further analyses of microorganism content within the patina layers. Additional geochemical analyses were carried out using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) in the geochemistry laboratories of the Geological Survey of Israel. A stereoscopic binocular and a light transmitting ore mineral microscope were also used to study the morphology, structural features and thin sections of the rock (see

Fig. 1C for sample locations).

3. Results

3.1. Rock-tablet

The general color of the fine-grained JI rock-tablet is medium gray. The gray color was observed in fresh breakage of the rock and in the samples of the drilling material. A fissure, less than 0.5 mm in width, runs across the central part of the tablet parallel to the broken upper edge, crossing ten letters in four lines (

Fig. 1B). The fissure begins in the 8th line and descends at an angle of 18° toward the left margin of the 11th line (

Fig. 1A and B). The tablet broke into two separate pieces along this fissure.

Petrographic analysis reveals that the rock, from which the tablet was produced, is an arkosic sandstone (

Fig. 2) composed mainly of unsorted sub-angular quartz grains 50–500 μm in size, and angular to sub-rounded unsorted feldspar grains, up to 100 μm in size. Thin section analyses of the rock material indicate that it is composed of: quartz (35%), feldspars (albite and orthoclase; 55%), epidote (3%), chlorite (1%), rutile and sphene (up to 1%), iron oxides and opaques (2–5%). A similar composition was obtained by XRD examination (

Fig. 3), however, the results are slightly different (e.g. here we note the presence of calcite and illite) because the XRD samples may have included material from the patina.

Many of the incised letters on the tablet exhibit defects in shape at the edges. These defects are due to the detachment of quartz and feldspar grains during subsequent weathering of the sandstone. Illuminating the tablet with ultraviolet light (

Newman, 1990) did not exhibit the characteristic glow that would indicate fresh engraving scars.

According to the chemical analysis by ICP-AES, the oxide composition of the rock (samples Z-10 to Z-12;

Fig. 1B) from which the tablet was engraved is (% oxides; normalized to 100%): SiO

2 – 60; CaO – 13; Fe

2O

3 – 5.5; Al

2O

3 – 11.5; Na

2O – 3.0; MgO – 2.5; K

2O – 1.8; P

2O

5 – 0.3; MnO – 0.1; TiO

2 – 0.7; SO

3– <0 .1.="" p="">

3.2. Patina

There are two areas on the tablet, one just above and to the left of the crack and the other just below and to the right of the crack, that lack a patina and so were almost certainly cleaned since the tablet's discovery. The patinated areas can be differentiated by their pale orange-brown color. The left lower part retains black to orange-brown as well as light beige patina layers up to 2 mm thick that cover the tablet and the inscription (

Fig. 4). The first layer attached to the rock is a thin, up to 1 mm thick, metallic black orange-brown iron oxide layer that covers the surfaces of the tablet and the engraved letters. In places the black and orange-brown layers alternate, occurring one next to the other. As the rock-tablet contains about 5% iron oxides, we suggest that the formation of both black and brown layers may be related to natural geo-biological weathering processes. The overlying and uppermost layer, orange-brown to light beige in color and up to 1 mm thick, is found mostly within the letters but also on the surfaces that were partly cleaned. The black orange-brown patina forms a continuous cover on the surface of the tablet as well as within the grooves of the letters (

Fig. 5). Some natural bleaching and incipient light patina formation (light gray zone just below the surface of the tablet) due to exposure to the air near its inscribed surface is also evident. Results of the SEM–EDS analysis of samples from the patina are presented in

Table 1. We analyzed nine samples (

Fig. 1C;

Table 1) using the SEM–EDS backscattered method for detecting heavy elements. We did not detect the presence of any element, such as Cr and V, which would have indicated the use of modern tools in the engraving process.

- Table 1. The occurrence of carbon ash particles and gold globules within the patina of the Jehoash Inscription tablet based on SEM–EDS analysis

| Sample number | Carbon ash | Gold globules | Iron oxides | Miscellaneous |

|---|

| Z-1 | Common; 10–30 μm | Abundant; 1 μm | | Rare; monazite |

| Z-2 | | Abundant; 0.5–1 μm | Rare; angular; 10 μm | |

| Z-3 | | Common; 1–4 μm | | |

| Z-4 | Common; 10–50 μm | | | |

| Z-5 | Common; 10–30 μm | Abundant; 1–4 μm | Common; 1–3 μm | Rare; clay |

| Z-6 | Common, 10 μm | | Common; 10 μm | |

| Z-7 | Abundant; 60–100 μm | | | |

| Z-8 | | | | Silica; calcsilicate |

| Z-9 | | | | Rare; monazite, clay |

- All samples are from the front of the tablet, however, Z-8 is taken from the lower back of the tablet. Abundant = >10 particles/mm2; common = 4–10 particles/mm2; rare = <4 mm="" particles="" sup="">2

.

Full-size table

The patina is composed of Si, O, Ca, Al, Mg, K and Fe. Many rectangular and spherical carbon ash particles 20–100 μm (

Fig. 6) were found, as well as a trace amount of pure gold globules 1–4 μm in diameter (

Fig. 7). Some gold globules were alloyed with about 2.5% copper and 3.2% iron. Sub-angular iron particles, 3–10 μm in size, were also found in the patina and these particles contain oxygen which clearly implies oxidation. The particles are devoid of any other element usually found in modern tools, and may have belonged to the scriber's tools used in the engraving. Some platy idiomorphic feldspar crystals of about 100 μm and some sub-angular quartz grains were observed in the patina. The light patina is composed mostly of quartz, feldspar, carbonate and iron oxide with a small amount (less than 1%) of clay cations Na, Al, Mg and K. The average contents of the oxides in the patina measured and calculated by SEM–EDS are (% oxides; normalized to 100%): SiO

2 – 53; CaO – 16; Fe

2O

3 – 18; Al

2O

3 – 5.5; Na

2O – 2.5; MgO – 2; K

2O – 1. Compared to the rock-tablet the patina is enriched with Fe

2O

3 by about 12% and CaO by 3%.

The iron concentration in the patina is about three times more than in the rock itself. The mineralogic composition of the patina, investigated by XRD analysis (

Fig. 8), includes quartz, calcite, dolomite and feldspar in a texture (confirmed by the SEM–EDS) of interlocking grains within a matrix of calcite.

The SEM–EDS analysis revealed that the patina contains carbon ash particles of 10–100 μm in size.

Fig. 6 is an example of such particles whose chemical composition is pure carbon. It should be noted that, based on SEM–EDS analysis, the patina contains only 5.5% Al

2O

3, 1% K

2O and rare monazite. Plagioclase crystals are common, suggesting that the clay content of the patina is very low.

3.3. Age determination of the patina

The carbon ash particles are admixed within the patina, firmly and intimately associated with the other particles (

Fig. 4 and

Fig. 6). Samples of the patina were taken by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and sent for radiocarbon dating to the Beta Analytic Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory in Miami, Florida, USA (

Table 2). According to their report from June 5, 2002, the patina samples were combined into a single sample. The surface area was increased as much as possible and the sediment was dispersed and pretreated by hydrochloric acid (HCl) that was applied repeatedly to ensure the absence of carbonates and to separate out the carbon ash particles. According to the laboratory report, the sample provided sufficient carbon for an accurate measurement and the AMS analysis proceeded normally. The conventional radiocarbon age is 2250 ± 40 years BP whereas the calibrated radiocarbon age was calculated at 2340–2150 Cal BP.

- Table 2. Radiocarbon age determination of the patina of the Jehoash Inscription tablet

| Sample data | Measured radiocarbon age | 13C/12C ratio | Conventional radiocarbon age |

|---|

| Report date: 6/5/02 |

| Material received: 5/20/02 |

| Beta – 167445 | 2190+/−40 BP | −21.1‰ | 2250+/−40 BP |

| Sample: BB | | | |

| Analysis: AMS | | | |

| Material/pretreatment | Patina/acid and solvent washes | | |

| 2 Sigma calibration | Cal BC 390–200 (Cal BP 2340–2150 | | |

- Full-size table

-

3.4. Gold globules

Gold globules that we detected in the patina using backscattered SEM–EDS, are minute, usually 1–2 μm in diameter (

Fig. 7) and were found in four of the nine samples taken from the patina. The gold is in the form of individual globules of well-sorted size. There are approximately 10 globules per mm

2 in each of the four patina samples (

Table 1). The total weight of the globules in the patina is calculated to be to less than 0.001 g for the entire tablet.

3.5. Microcolonial fungi

Microcolonial fungi (MCF), known to concentrate and deposit manganese and iron, play a key role in the alteration and biological weathering of rocks and minerals (

Staley et al., 1982 and

Gurbushina, 2003). They are microorganisms of high survivability, inhabiting rocks in extreme conditions, and are also known to survive in subsurface and subaerial environments. Long-living black yeast-like fungi form pitted embedded circular structures of 5–500 μm in size (

Fig. 9 and

Fig. 10) (

Krumbein, 2003,

Krumbein and Jens, 1981 and

Sterflinger and Krumbein, 1997). The MCF structures (

Fig. 9) were found inside the last letter of the 14th row of the tablet. There is morphological continuity between the patina of the rock surface itself and the grooves of the letters (

Fig. 5). The black orange-brown thin layers (films) of iron-oxide patina are the product of geomicrobiogenic activity that covers all surfaces of the tablet.

A scanning electron micrograph (

Fig. 10) of the border section between the patina and crack in the tablet shows circular pits (P) from microbial attack and fungal hyphae (H) indicating fungal growth and patination. A hypha is one of the individual tubular filaments or threads that make up the mycelium of a fungus. The fungi, belonging to a group of dematiaceous black yeasts, were identified as

Coniosporium sp. and related species. Clear evidence of biopitting can be found in recent outcrops in the nearby deserts of Judea, the Negev and Sinai. The structures in the Jehoash Tablet near the lettering zone are significant in that they are almost identical, although not as clear, as those cited by

Krumbein, 2003 and

Krumbein and Jens, 1981 and

Sterflinger and Krumbein (1997), and can be explained by prolonged exposure to atmospheric conditions.

4. Discussion

Layered platy arkosic sandstones occur in Cambrian formations exposed in southern Israel and in southwest Jordan (

Bender, 1968) and were readily available to stone workers in Judea in ancient times. Such rocks are found south of the Dead Sea, in the Timna area and in southern Sinai, mainly in the Shechoret Formation (

Weissbrod, 1987). In the Temple of Serabit el-Khadem in southern Sinai, many of stelae with hieroglyphic inscriptions from the Middle and New Kingdoms are carved from arkosic sandstone of the upper part of the Shechoret Formation.

Goren et al. (2004) determined that the tablet was engraved in graywacke. However, there is no graywacke in Israel or Sinai.

The patina coating the tablet carrying the inscription is composed of elements derived from the tablet itself (quartz and feldspar grains) as well as accretion from the environment (calcite and dolomite deposits, carbon ash particles, and gold globules). The patina from the back of the tablet is composed mostly of quartz and some carbonate. This siliceous-carbonate material could be an original vein filling along a bedding plane or a joint in the original rock, similar to those found in the Cambrian clastic rocks exposed in southern Israel and Sinai, and may represent a natural rock fissure along which the rock was detached for further processing as is the case in many quarries. No indications of adhesive materials or other artificial substances that could indicate addition, pasting, or dispersion of artificial patina on the inscribed face of the tablet have been observed.

The occurrence of pure gold globules (1–4 μm) is evidence of the melting (above 1000 °C) of gold artifacts or gold-gilded items. Gold powder comprised of globules 1–4 μm in diameter does not exist in the modern gold market, where gold globules have a wide range of sizes, the smallest diameter being 500 μm. On the other hand, gold powder, or gold dust, with an average size between 70 and 80 μm has an angular, flaky shape. Native gold dust from Sardis, Turkey contains irregular flattened flakes with rounded edges, 100–500 μm in size, but not globules (

Geckinli et al., 2000). According to

Meeks (2000), pure gold globules of 3–300 μm in diameter were found in the production and refining site of Sardis resulting from melting processes. One would thus expect many gold globules of various sizes to occur in clustered aggregates in the patina if it was of recent origin. This is clearly not the case. The small amounts detected would be difficult to produce within any artificial patina. Both the occurrence of carbon ash particles and gold globules in the patina are suggestive of a thermal event. It is proposed that the ‘apparent’ radiocarbon age of 2250 years BP is an average of a mixture of older and younger carbon fragments that have been incorporated into the patina over time, thus implying that there was more than one thermal event.

The microbiogenic patina is dense, coating all surfaces as well as the engraved letters, and indicates growth over extended periods of time. A Nabataean flint artifact from Avdat, southern Israel, 2000 years old (

Krumbein, 1969) shows the following identical features to those found in the JI tablet: microcolonial fungi, a black orange-brown coloration and pitted circular structures.

Recently, the oxygen isotopic composition of the carbonate of the patina was analyzed and the results used to suggest that the JI tablet was not authentic (

Goren et al., 2004). This conclusion was based on the assumption that the presence of oxygen in the carbonate could be explained by precipitation from meteoric groundwater in the Jerusalem area. The data of

Goren et al.'s (2004) four analyses of patina taken from the surface of the tablet could, however, be interpreted differently. Two of their four results exhibit

δ18O values (−1.7‰ and −0.9‰, PDB) that are anomalously enriched compared to local cave precipitates. However, these values are exactly what are to be expected from marine carbonate material. Exposures of Cretaceous marine carbonates are abundant in Jerusalem and provide a majority of its building stone. It is probably marine carbonates that were found within the JI tablet patina, with the particles derived from the weathering of these exposed rocks and deposited by wind. Indeed, well-preserved marine carbonate microfossils, such as Cretaceous to Eocene foraminifera, occur in abundance in everyday dust in Jerusalem (

Ehrenberg, 1860,

Ganor, 1975 and

Ganor et al., 2007) as well as in the local soils.

Goren et al.'s (2004) other two reported

δ18O values (−8.4‰ and −7.3‰) are depleted relative to modern carbonate formation data (−4‰ to −6‰) (

Bar-Matthews and Ayalon, 1997). However, there are many ways that isotopically depleted carbonate can be generated and incorporated in a genuine patina, such as the process of decarbonation, that would indicate thermal events. Thermally induced decarbonation reactions of calcite and dolomite with the quartz or feldspar in arkosic sandstone or in the soil would result in residual carbonate with lowered

δ18O values (

Faure, 1986). Isotopic depletion, due to thermal metamorphism, occurs in lime-rich soils when they are intruded by igneous bodies (

Katz et al., 1998). In the vicinity of Jerusalem, widespread lowering of

δ18O values in normal marine carbonates of the Hatrurim Formation took place by decarbonation during (non-igneous related) thermal metamorphism (

Kolodny and Gross, 1974). Calcite from the Negev oil shales exhibits

δ18O values of −0.5‰ to −2‰ PDB; however, after heating these oil shales to 700–800 °C, depletion of

δ18O values (−5.2‰ to −10.2‰ PDB) is obtained in the residual carbonate (

Yoffe et al., 2002). Moreover, light oxygen isotope values are known to be deposited in the Judean mountains during years of high precipitation, that is, over 1000 mm of rainfall per year (e.g. see

Fig. 6,

Bar-Matthews and Ayalon, 1997). According to

Kolodny et al. (2005), the dominance of the source effect in determining the oxygen isotopic composition of speleothems in the Levant reduces the power of

δ18O as an independent climatic indicator. Because of the lack of knowledge of the mineralogical association of the oxygen isotopes, the burial and custodial history of the JI tablet, the oxygen data of

Goren et al. (2004) is completely moot. No conclusions can be drawn from the oxygen isotope data. Further exposure, even for short periods of time, to surface conditions with varying amounts of rainfall, high temperature regimes and consecutive evaporation events may significantly alter oxygen isotope ratios. In addition, we would like to note that the modern cleaning processes of the JI tablet depending on the cleaner used could easily change the expected oxygen fractionation values in the patina.

5. Conclusions

Our analyses strongly support the authenticity of the Jehoash tablet and its inscription. All evidences indicate that the production of the tablet and the carving of its inscription occurred at essentially the same time. The critical evidence is as follows: (1) the central fissure and the upper breakage cut across several lines and letters and the patina extends down along the margins of the broken faces, (2) quartz and feldspar grains found within the patina are weathered from within the rock, (3) the patina is dense, microbiogenic and is indicative of growth over extended periods of time, (4) the two patina layers attached to the rock (black orange-brown and an upper lighter-colored one) that cover the tablet and inscription includes ash particles and minute, well-sorted globules of pure gold, a product of melting, (5) the age of the carbon ash interlocked within the patina is approximately 2250 years BP according to radiocarbon dating and, (6) no modern elements related to the use of modern tools were found.

6. Note added in proof

Fig. 4,

Fig. 5,

Fig. 6,

Fig. 7,

Fig. 8 and

Fig. 9 modified from Dahari, U., 2004. The James Ossuary: Ancient Relic or Modern Forgery? Cornerstone University Press, Symposium, 12 May 2004.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Honigstein, Ministry of National Infrastructures, Oil and Gas Section, Jerusalem, Israel, Dr. K. Kojonen, Geological Survey of Finland, and, Dr. A. Shimron, Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, for their insightful reviews of an earlier version of the manuscript and suggestions for improvement. Constructive comments by two anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged. We are grateful to M. Dvorachek, Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, for help with the SEM–EDS work and Susan Feldman, Scarsdale, New York, for technical assistance. We thank Dr. Y. Natan, Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, for identifying the carbon ash particles in the patina. WEK acknowledges the help of the ICBM electron microscopy unit and the Soil Science Department of Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg for microscopy and X-ray diffractometry as well as the Institute of Crystallography of the Würzburg University.

References

- Bar-Matthews and Ayalon, 1997

- M. Bar-Matthews, A. Ayalon

- Late quaternary paleoclimate in the eastern Mediterranean region from stable isotope analysis of speleothems at Soreq Cave, Israel

- Quaternary Research, 47 (1997), pp. 155–168

-

|

|

- Bender, 1968

- F. Bender

- Geologie Von Jordanien-Beitraege Zur Regionalen Geologie der Erde, vol. 7Gebrueder Borntraeger, Berlin (1968)

- Cohen, 2005

- C. Cohen

- Yeho'ash Inscription – a new addition: philological aspects. Abstract

- The 14th World Congress of Jewish Studies, Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, Jerusalem (2005) p. 5

- Cohen, 2007

- Cohen, C., 2007. Biblical Hebrew philology in the light of research on the new Yeho'ash Royal Building Inscription. In: Lubetski, M. (Ed.), New Seals and Inscriptions: Hebrew, Idumean, and Cuneiform, Sheffield, pp. 222–286.

- Cross, 2003

- F.M. Cross

- Notes on the forged plaque recording repairs to the temple

- Israel Exploration Journal, 53 (2003), pp. 119–122

-

- Ehrenberg, 1860

- Ehrenberg, C.G., 1860. Über einen sehr merkwürdigen Meteorstaubfall in Jerusalem mit großem Orkan am 8-9. Februar d, Jahres, Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, vol. 121, pp. 137–151.

- Faure, 1986

- G. Faure

- Principles of Isotope Geology

- (second ed.)John Wiley and Sons, New York (1986)

- Freedman, 2004

- D.N. Freedman

- Don't rush to judgment: Jehoash inscription may be authentic

- Biblical Archaeology Review, 30 (2004), pp. 48–51

- Ganor, 1975

- Ganor, E., 1975. Atmospheric Dust in Israel: Sedimentological and Meteorological Analysis of Dust Deposition. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

- Ganor et al., 2007

- Ganor, E., Ilani, S., Kronfeld, J., Rosenfeld, A., Feldman, H.R., 2007. Environmental dust as a tool to study the archaeometry of patinas on ancient artifacts in the Levant, In: Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, vol. 39, Geological Society of America, Denver, p. 574.

- Geckinli et al., 2000

- A.E. Geckinli, H. Ozbzl, P.T. Craddock, N.D. Meeks

- King Croesus' gold, excavation at Sardis and the history of gold refining

- ,in: A. Ramage, P. Craddock (Eds.), Examination of the Sardis Gold and the Replication Experiments, Monograph Volume 11, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, in association with the British Museum Press, Cambridge, New York (2000), pp. 184–199

- Goren et al., 2004

- Goren, Y., Ayalon, A., Bar-Matthews, M., Schilman, B., 2004. Authenticity examination of Jehoash inscription. Journal of the Institute of Arcahaeology of Tel Aviv University, 31, 3–16.

- Gurbushina, 2003

- A. Gurbushina

- Microcolonial fungi: survival potential of terrestrial vegetative structures

- Astrobiology, 3 (2003), pp. 543–554

- Ilani et al., 2002

- S. Ilani, A. Rosenfeld, M. Dvorachek

- Archaeometry of a stone tablet with Hebrew inscription referring to repair of the house

- Israel Geological Survey Current Research, 13 (2002), pp. 109–116

- Katz et al., 1998

- B. Katz, R.D. Elmore, M.N. Engel

- Authigenesis of magnetite in organic-rich sediment next to a dike: implications for thermoviscous and chemical remagnetizations

- Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 163 (1998), pp. 221–239

- Kolodny and Gross, 1974

- Y. Kolodny, S. Gross

- Thermal metamorphism by combustion of organic matter: isotopic and petrological evidence

- Journal of Geology, 82 (1974), pp. 489–506

- Kolodny et al., 2005

- Y. Kolodny, M. Stein, M. Machlus

- Sea-rain-lake relation in the last glacial east Mediterranean revealed by δ18O–δ13C in Lake Lisan aragonites

- Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 69 (2005), pp. 4045–4060

-

|

|

- Krumbein, 1969

- W.E. Krumbein

- Über den Einfluß der Mikroflora auf die exogene Dynamik (Verwitterung und Krustenbildung)

- Geollogisches Rundschau, 58 (1969), pp. 333–363

- Krumbein, 2003

- Krumbein, W.E., 2003. Patina and cultural heritage–a geomicrobiologist's perspective, In: Proceedings of the European Common Conference Cultural Heritage Research: A Pan – European Challenge, vol. 5, pp. 39–47.

- Krumbein and Jens, 1981

- W.E. Krumbein, K. Jens

- Biogenic rock varnishes of the Negev Desert (Israel) an ecological study of iron and manganese transformation by cyanobacteria and fungi

- Oecologia, 50 (1981), pp. 25–38

-

|

- Meeks, 2000

- Meeks, N.D., 2000. Scanning electron microscopy of the refractory remains and the gold. In: Ramage, A., Craddock, P. (Eds.), Examination of the Sardis gold and the replication experiments, Monograph Volume 11, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, in association with the British Museum Press, Cambridge, pp. 99–156.

- Newman, 1990

- Newman, R., 1990. Weathering layers and the authentification of marble objects, In: True, M., Podany, J. (Ed.), Art Historical and Scientific Perspectives on Ancient Sculpture, The Journal of the Paul Getty Museum, J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, pp. 263–282.

- Rosenfeld et al., 2005

- Rosenfeld, A., Ilani, S., Kronfeld, J., Feldman, H.R., Telem, E.M., 2005. Archaeometric analysis of the “Jehoash Inscription” stone describing the renovation of the First Temple of Jerusalem, In: Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, vol. 37, Salt Lake City, p. 278.

- Sasson, 2004

- V. Sasson

- Philological and textural observations on the controversial Jehoash inscription

- Ugarit-Forschungen, 35 (2004), pp. 573–587

- Staley et al., 1982

- J.T. Staley, F.E. Palmer, J.B. Adams

- Microcolonial fungi: common inhabitants on desert rocks?

- Science, 215 (1982), pp. 1093–1095

-

- Sterflinger and Krumbein, 1997

- K. Sterflinger, W.E. Krumbein

- Dematiaceous fungi as the main agent of biopitting on Mediterranean marbles and limestones

- Geomicrobiology Journal, 14 (1997), pp. 219–231

- Weissbrod, 1987

- Weissbrod, T., 1987. The Paleozoic of Sinai and the Negev. In: Gvirtzman, G., Gradus, A., Beit-Arie, Y., Har-El, M. (Eds.), Sinai Physical Geography, Tel Aviv, pp. 43–58.

- Yoffe et al., 2002

- O. Yoffe, Y. Nathan, A. Wolfarth, S. Cohen, S. Shoval

- The chemistry and mineralogy of the Negev oil shale ashes

- Fuel, 81 (2002), pp. 1101–1117

-

|

|

- Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 914 472 0528.

Copyright © 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

- Your search for "jehoash tablet " would return 3 results on ScienceDirect. Here are the top results:

- Vasilike Argyropoulos , Kyriaki Polikreti , Stefan Simon , Dimitris Charalambous

- Ethical issues in research and publication of illicit cultural property

- Journal of Cultural Heritage, Volume 12, Issue 2, April–June 2011, Pages 214–219

- Original Research Article

- Environmental dust: A tool to study the patina of ancient artifacts

- 2009, Journal of Arid Environments

-

Close

- E. Ganor , J. Kronfeld , H.R. Feldman , A. Rosenfeld , S. Ilani

- Environmental dust: A tool to study the patina of ancient artifacts

- Journal of Arid Environments, Volume 73, Issue 12, December 2009, Pages 1170–1176

- Original Research Article

- Archaeometric analysis of the “Jehoash Inscription” tablet

- 2008, Journal of Archaeological Science

-

Close

- S. Ilani , A. Rosenfeld , H.R. Feldman , W.E. Krumbein , J. Kronfeld

- Archaeometric analysis of the “Jehoash Inscription” tablet

- Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 35, Issue 11, November 2008, Pages 2966–2972

- Original Research Article