by

Damien F. Mackey

Owing to the parlous state of the

conventional archaeology and chronology, one has to dig very deeply to ‘lay

spade’ on the true era of King Solomon of Israel. Quite useless have proven to

be the shallow efforts of contemporary archaeologists like Israel Finkelstein

and his colleagues. These, scratching around in an impoverished phase of the

Iron Age in hopeful pursuit of - or is that hopeful good riddance to? -

evidence for kings David and Solomon, and finding absolutely nothing of

relevance, then boldly proclaim themselves to have destroyed the likes of

Solomon.

We have already learned about Berlin

chronologist Eduard Meyer’s most unfortunate off-setting of Egyptian history in

relation to the biblical record - his artificial Sothic theory - and how it has

served to push King Solomon’s Egyptian contemporaries, the Eighteenth Dynasty’s Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, into the C15th

BC, about 500 years before Solomon.

And yet another chronologist - what

is it about them? - Dominican Fr. Louis-Hugues Vincent, of the École Biblique

in Jerusalem, has been instrumental in throwing right out of kilter the

Palestinian archaeology, so that, for instance, the destruction of Jericho is

now dated about a millennium before the time of Joshua (when the destruction actually

occurred).

Quite a disaster!

In 1922 Fr. Vincent, a

pottery-chronologist to be specific, worked out this new arrangement in

partnership with his very good friend W.F. Albright – sadly, because Albright

was one who was at least capable of, from time to time, arriving at brilliant

conclusions that burst out of the suffocating straightjacket of conventional

thinking.

Another era needing to be tied to

David and Solomon is, as we have found, c. 1800 BC (conventional dating)

Syro-Mesopotamia. This is the era of King Hammurabi of Babylon and Zimri-Lim of

Mari, amongst many others (some biblical identifiable to the Davidic/Solomonic

era). Most confusingly, the Solomonic era recurs again in the conventional

system in c. C15th BC Syro-Mitanni.

At least this synchronises with the

C15th BC (mis-)placement of Egypt’s Eighteenth

Dynasty.

Now I, just to ‘complicate’ matters

even further, am going to suggest that yet another era, Sumerian c. 2100 BC,

must also be merged with Hammurabi and the golden age of Solomon.

Since what follows on this score is brand new

material, it will be presented only as a non-detailed working hypothesis at

this early stage.

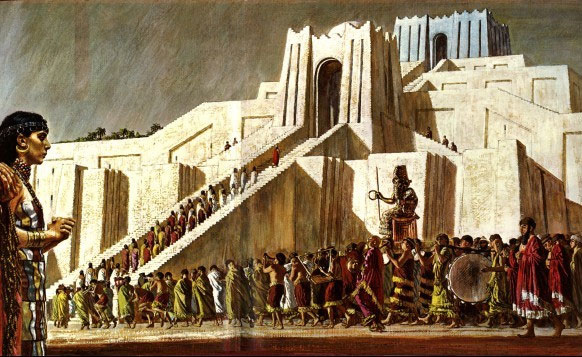

UR

NAMMU MAY BE HAMMURABI

“300 years before

Hammurabi, King Ur-Nammu founded the 3rd Dynasty of Ur, and laid the foundation

of the Ziggurat dedicating it to the revered Moon God; Nanna.

Ur-Nammu is credited to have established the first legal

code in history. In it, he put laws, rules, and guidelines that defined the

rights of the individual, the consequences of disobedience, and forms of

punishments in violation of the laws; with two main currencies for exchange,

the life of the individual and/or their money.

It is worth noting that the similarities between

Ur-Nammu's Code and Hammurabi Code are many, including the depiction of the

king and the sitting god on the throne with a scepter in one hand and a ring

and a rod in the other. …”.

Regarding the depiction, now of Ur Nammu, now of

Hammurabi, I actually find these to be so alike that I have begun to wonder if

Ur Nammu was in fact Hammurabi.

With Hammurabi now moved down to the time of King

Solomon, then one might expect a similar necessary downward shifting of Ur

Nammu.

Given that the - albeit most significant - Ur III

dynasty was hardly recognised by the later Mesopotamians (see below) had led me

to the conclusion that the dynasty was in need of an alter ego dynasty. Ur III presents historians with the conundrum of

a super-abundance of documentary materials, on the one hand, coupled with a

seeming total disinterest in the dynasty by later Mesopotamians, on the other.

Marc Van de Mieroop writes of both the massive amount of documentation from the

period and the strange disinterest in Ur III by the later generations (A History of the Ancient Near East, p.

72):

Virtually no period of ancient Near Eastern history presents the historian with

such an abundance and variety of

documentation. Indeed, even in all of the ancient histories of Greece and Rome, there are few periods where a similar profusion

of textual material is found. ….

But, despite this incredible fact:

Remarkable is the lack of interest in this period by

later Mesopotamians when compared to how long they remembered Akkad's

kings were remembered. In the first centuries of the second millennium, Ur

III rulers were known primarily through the school curriculum. ….

Obviously this cannot be right. We are talking here

about a dynasty that was responsible for the construction of the magnificent

ziggurat at Ur. Kings of this sort of grandeur are not going to be virtually

forgotten by later generations. The situation demands that Ur III be merged

with another dynasty. I have been trying to find that partnership match in the

Akkadian dynasty. However, I now think that I should have been looking much

further down the historical track, to the First Dynasty of Babylon, Hammurabi’s

dynasty.

Ur Nammu to be merged with Hammurabi.

With Ur Nammu dated to c. 2100 BC, then his famous

laws could rightly be considered to have preceded those of Moses by about half

a millennium. However, if Ur Nammu is lowered on the time scale to fold into

Hammurabi, then it would be more likely that the Torah of Moses, filtered

through, say, a King David, had influenced Ur Nammu.

Whilst Ur Nammu’s laws are considered to be less

harsh than Hammurabi’s, this could be simply due to alterations over time, or

different uses in different locales, e.g. Ur and Babylon.

“Many people may not know it, but they have heard part

of Hammurabi’s Law Code before. It is where the fabled “eye-for-an-eye”

statement came from. However, this brutal way of enforcing laws was not always

the case in ancient Mesopotamia, where Hammurabi ruled. The Laws of Ur-Nammu

are much milder and project a greater sense of tolerance in an earlier time.

The changing Mesopotamian society dictated this change to a harsher, more

defined law that Hammurabi ruled from. It was the urge to solidify his power in

Mesopotamia that led Hammurabi to create his Law Code.

It must first be noted that the Laws of Ur-Nammu were

written some time around 2100 B.C., around three hundred years before

Hammurabi’s Code. Because of this, The Laws of Ur-Nammu are much less defined

in translation as well as more incomplete in their discovery. However, it is

apparent from the text that these laws were concerned with establishing

Mesopotamia as a fair society where equality is inherent. In the prologue

before the laws, it is stated that “the orphan was not delivered up to the rich

man; the widow was not delivered up to the mighty man; the man of one shekel was

not delivered up to the man of one mina.” This set forth that no citizen

answered to another, or even that each citizen answered to each other, no

matter their wealth, strength, or perceived power. ….

There are many skeptics today that argue that the

laws contained in the Old Testament are written on the basis of earlier

Sumerian and Babylonian law codes.

The

purpose of such theses is to question the Divine inspiration of Scripture and

to demonstrate that the underlying principles in these texts are merely human,

and dare I say, imitative in nature.

For

someone who does not have a grasp on the subject, these theses can be quite

persuasive at first sight. To give a popular example; it is possible to find

the maxim "eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand" (Exodus

21:23, ESV) in the Code of Hammurabi which dates to a period at least 400 years

prior [sic]: “If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put

out” (Article 196) or "If a man knock out the teeth of his equal, his

teeth shall be knocked out." (Article 200).

What’s

more, these similarities are not limited to the laws of Hammurabi only. For

example, the Code of Ur-Nammu, which is at least 300 years older and thought to

be by some the oldest Law code, states: “The man who committed the murder will

be killed.” (Article 1) Compare this to the Mosaic Law which tells us that

"Whoever strikes a man so that he dies shall be put to death.” (Ex. 21:12,

ESV).

Such

similarities often lead to a very simplistic preliminary judgment that the Old

Testament has perhaps copied these laws. Similarities may indeed exist, but

similarity is not synonymous with causality. Moreover, similarities in wording

and expression should be fairly normal for these laws, considering they

all proceed from a common age and geography. Perhaps it would be more

appropriate to say that similar laws point to humanity’s shared concern for

justice more than to a mere causality.

To me,

what is truly fascinating is the astonishing picture one is left with upon

cross-examining the underlying principles of these law codes. I would go so far

as to say that the laws of Moses show great differences with the spirit of

Mesopotamian laws codes. In fact so much so, that I honestly believe that many

do not realize the revolutionary character of the Mosaic laws for its day and

age. In the following paragraphs I will be contrasting the differences between

the Mesopotamian Codes and the Mosaic Law under four main headings, with

special attention given to the Code of Ur-Nammu:

1) DIVINE SOURCE VS HUMAN SOURCE

The

Introduction to the Code of Ur-Nammu reads as follows:

“After An and Enlil had turned over the Kingship of Ur

to Nanna, at that time did Ur-Nammu, son born of Ninsun, for his

beloved mother who bore him, in accordance with his principles of equity and

truth... Then did Ur-Nammu the mighty warrior, king of Ur, king

of Sumer and Akkad, by the might of Nanna, lord of the

city, and in accordance with the true word of Utu, establish equity in the

land; he banished malediction, violence and strife, and set the monthly Temple

expenses at 90 gur of barley, 30 sheep, and 30 sila of

butter.”

From

this statement, it is understood that this law code emerged at the initiative

of King Ur-Nammu. The reason for the writing of this law is not necessarily a

particular god but the king's own will. Although the king emphasizes that some

deities may have provided spiritual support and direction to him, this is quite

different from the claim of divine origin made in the Mosaic Law. Contrast this

with the introduction and direct voice of God found in Exodus 20:1-2, “And God

spoke all these words, saying “I am the LORD your God, who brought

you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” (ESV)

It is

evident that Ur-Nammu and other similar ancient laws were recorded at the

initiative of the kings themselves. Whereas the Old Testament text clearly

states that the laws came directly from God. In this context, the Old Testament

is making a revolutionary claim, a claim of divine legal authority that had not

been heard of until that day.

2) THE CONCEPT OF EQUALITY AND THE REASONS FOR PUNISHMENT

In the

Mesopotamian understanding of justice, the aim of the law is to bring order to

society. But it is quite difficult to say that this method is equitable to

today's understanding of equality under the law. For example, in the case of

Hammurabi’s Code, those who have a higher social class undergo lighter forms of

punishment compared to those who commit the same crime but belong to a lower

class. Compare the three levels of class-based-punishment found in articles 202,

203, and 204 of the Code of Hammurabi:

-

Article 202: If any one strike the body of a man higher in rank than he, he

shall receive sixty blows with an ox-whip in public.

-

Article 203: If a free-born man strike the body of another free-born man or

equal rank, he shall pay one gold mina.

-

Article 204: If a freed man strike the body of another freed man, he shall pay

ten shekels in money.

The

Mosaic law is quite different in this regard, because punishment depends on the

nature of the crime rather than the social class. One of the most important

reasons for this is that the law of Moses is not based on class sensibilities.

Rather,

it is based on the sanctity of each individual life created in “the image of

God.” Its concept of law is anchored in the idea of “God’s holiness"

rather than the protection of the socially elite: "You shall be holy to

me, for I the LORD am holy and have separated you from the peoples, that you

should be mine.” (Leviticus 20:26, ESV)

3) A DIFFERENCE IN FOCUS WHEN IT COMES TO CAPITAL PUNISHMENT AND MONETARY

COMPENSATION

Perhaps

one of the most striking differences between the Old Mesopotamian codes and the

Mosaic Law is the nature of punishments for crimes committed against human

dignity. In the most general sense (though there are some exceptions), in the

laws of Ancient Mesopotamia crimes committed against human dignity are punished

with fines, while crimes against property are punished with death. In the

Mosaic Law we observe an opposite approach. For while sins against human

dignity are punishable by death, property crimes are converted into fines. The

following examples make this difference quite obvious:

-

Ur-Nammu, Article 2: “If a man commits a robbery, he will be killed.”

-

Mosaic Code, Exodus 22:1: “If a man steals an ox or a sheep, and kills it or

sells it, he shall repay five oxen for an ox, and four sheep for a sheep.”

(ESV)

-

Ur-Nammu, Article 3: “If a man commits a kidnapping, he is to be

imprisoned and pay 15 shekels of silver.”

-

Mosaic Code, Exodus 21:16: “Whoever steals a man and sells him, and anyone

found in possession of him, shall be put to death.” (ESV)

-

Ur-Nammu, Article 28: “If a man appeared as a witness, and was shown to be

a perjurer, he must pay fifteen shekels of silver.”

-

Mosaic Code: Deuteronomy 19:18-19: “The judges shall inquire diligently,

and if the witness is a false witness and has accused his brother falsely, then

you shall do to him as he had meant to do to his brother. So you shall purge

the evil from your midst.” (ESV)

4) GREAT DIFFERENCES IN PUNISHMENTS GIVEN TO WOMEN

The

position of women in ancient law codes is of course far from our 21st century

sensibilities. However, when we compare these laws with the Mosaic code, we do

find that the Mosaic code draws a more just and equitable line. For example, in

the Ur-Nammu code, a woman committing adultery is subjected to capital

punishment while the man is set free. In contrast, in the Mosaic Law both men

and women convicted of adultery are subject to capital punishment. In the

Ur-Nammu code the penalty given to a man who abuses a virgin is 5 shekels of

silver. In the Mosaic Code the punishment is 10 times harsher, 50 shekels.

Additionally, it was expected that the abusing man marry the virgin and lose

all his rights for divorce. This is, in case the virgin’s father were to accept

the arrangement. If the virgin’s father refused, she could continue to live

under her father’s protection.

The

culprit was expected to pay the dowry price regardless. This last measure

may seem rather strange and cruel to our modern ears, but what it meant to

achieve was to shame the perpetrator and insure the material support of the

woman for the rest of her lifetime. Here we can take a glance at such laws:

-

Ur-Nammu, Article 7: “If the wife of a man followed after another man and he

slept with her, they shall slay that woman, but that male shall be set free.

-

Mosaic Code, Leviticus 20:10: “If a man commits adultery with the wife of

his neighbor, both the adulterer and the adulteress shall surely be put to

death.” (ESV)

-

Ur-Nammu, Article 8: “If a man proceeded by force, and deflowered the virgin

female slave of another man, that man must pay five shekels of silver.”

-

Mosaic Code, Deuteronomy 22:28-29: “If a man meets a virgin who is not

betrothed, and seizes her and lies with her, and they are found, then the man

who lay with her shall give to the father of the young woman fifty shekels of

silver, and she shall be his wife, because he has violated her. He may not

divorce her all his days.” (ESV)

-

Mosaic Code, Exodus 22:16-17: “If a man seduces a virgin who is not betrothed

and lies with her, he shall give the bride-price for her and make her his

wife. If her father utterly refuses to give her to him, he shall pay

money equal to the bride-price for virgins.” (ESV)

In

conclusion, we observe many differences between the Mosaic law and Mesopotamian

codes. While the Mosaic code emphasizes that laws come directly from the Deity,

the texts of other civilizations emphasize that the laws are based on the

initiative of a ruler. While the Mosaic code is based on the holiness of God

and the sanctity and of human life, the laws of Mesopotamia are based on

preserving or protecting a particular social class or elite. While the Mosaic

code applies the death penalty to crimes against human dignity,

Mesopotamian laws implement this punishment to crimes mostly against property.

While the laws of Mesopotamia draw a highly prejudiced line against women, the

Mosaic code proves to be more equidistant. In short, the Mosaic code is quite

revolutionary for the times! So, where did this understanding of law come from?

I’m fully aware that this study in of itself doesn’t prove beyond a doubt the

Revelation of Scripture. However, it is plain to see that claims that the

Mosaic code is somehow an imitation or inspired from Mesopotamian texts are

rather simplistic and naive.

If

there is something definite, it is that the Mosaic code offers an innovative

thought approach unseen until its day. Definitely not seen in Mesopotamian

civilizations for sure. ....

As I made so bold to do in the case of the earlier

Akkadian dynasty, folding its two major king-names (Sargon and Naram-Sin) into

the one person (and identified as the biblical Nimrod), so I am now inclined to

do the same with Ur Nammu and the deified Shulgi, identifying these names as

the one mighty king.

My reason is that common situation according to

which scholars are not entirely sure whether to credit some new initiative,

building work, document, to Ur Nammu or to Shulgi - the same situation that

frequently arises in the case of Sargon II and Sennacherib (as we shall find) -

which can often mean that there is only the one king involved, but he is

represented by two different names.

Shulgi is supposed to have finished the famous

ziggurat of Ur begun by Ur Nammu.

The one combined king would then fold into the great

Hammurabi of somewhat similar reign length to Shulgi (more than four decades).

His father was Ur-Nammu (r.2047-2030 BCE), who

founded the Third Dynasty of Ur and helped to defeat the occupying forces of

the Gutians, and his mother was a daughter of King Utu-Hegel of Uruk (her name is not known) who

first led the uprising against the Gutian occupation.

Shulgi inherited a stable

kingdom after his father was killed in battle with the Gutians and

proceeded to build upon his father’s legacy to raise Sumer to great cultural heights.

A literate man, he reformed

the scribal schools and increased literacy throughout the region. He allocated

funds for the continued maintenance of the cities, improved the existing roads

and built new ones, and even instituted the first roadside inns so that

travelers could stop, rest, eat, and drink as they traveled (an innovation

later adopted by the Persian Empire). He declared himself a god during his lifetime

and seems to have been worshipped by the people following his death.

….

His reign is well documented

as he had many scribes making inscriptions of his accomplishments but this

documentation has been challenged on the grounds of inaccuracy. While it does

seem clear that Shulgi reigned well, the majority of the documents relating to

the details of his rule were those he ordered to be set down. Later chroniclers

would accuse him of impiety and falsification of records, but the

archaeological evidence seems to support his version of his reign fairly well.

In a single day, Shulgi ran 200 miles (321.8 km) through a great storm

in order to officiate at religious festivals in Ur and Nippur.

Early Reign and Shulgi’s Run

Ur-Nammu’s rule had stabilized

the region and enabled it to prosper following the expulsion of the Gutians

and, thanks to the poem The Death of Ur-Nammu and His Descent to the

Underworld, he had become an almost mythic hero shortly after his death.

His successor might be

expected to have struggled to distinguish himself from the former’s rule, but

this does not seem to be the case with Shulgi.

In order to ensure the

stability of his kingdom, he created a standing army which he formed into

specialized units for specific military purposes (an infantryman was no longer

just a `foot soldier’ but specialized in a certain tactic, formation, and

purpose on the field). He then drove this army against the remaining Gutians in

the region to avenge his father’s death and secure the borders.

To raise money for his army,

he initiated the unprecedented policy of taxing the temples and temple complexes which, though it

may have made him unpopular with the priests, could have bolstered his

popularity among the general populace who did not have to suffer an increase in

taxation.

Scholar Stephen Bertman

notes that, "Ur-Nammu’s imperialistic dreams were fulfilled by his son

Shulgi” in the expansion of the Kingdom of Ur from southern Mesopotamia near Eridu up the Tigris River valley to

Nineveh in the north (57). This area corresponds roughly to modern-day Kuwait

in the south to northern Iraq. The kingdom was maintained efficiently through

the unified central administration instituted by Ur-Nammu, which Shulgi

improved upon, and was protected and enlarged by the standing army which, since

it needed no mobilization, could respond quickly to any disturbance on the

borders. With his state secure, Shulgi could devote himself to encouraging art

and culture, as his father had done.

He introduced a national

calendar and standardized time-keeping so that the whole of his kingdom

recognized the same day and time, replacing the old method of different regions

reckoning dates and times in their own way. He also instituted agricultural

reforms and standardized weights and measures to ensure fair trade in the market place. Prior to

Shulgi’s reforms, prices varied – sometimes widely – between trade goods in Ur

and the same goods in Nippur. All documents were written in Sumerian (instead of the traditional

state language, Akkadian), perhaps in an effort to differentiate Shulgi’s reign

from those of the past.

….

Even so, he seems to have

purposefully presented himself to his subjects as a new Naram-Sin (r. 2261-2224 BCE) of Akkad, the last great ruler of the

Akkadian Empire. Ur-Nammu had also understood the value of

linking his reign to that of the legendary Akkadian kings, but Shulgi went

further in proclaiming himself a god, as Naram-Sin had also done, and signing

his name to documents with the divine determinative.

While his accomplishments were

many, he still seems to have felt that he was merely carrying on the policies

and building projects instituted by his father.

The scholar Paul Kriwaczek writes:

Construction work on Ur-Nammu’s ziggurats

continued well into his son’s reign, which left Shulgi with the problem of how

to establish his own superhuman persona in his people’s awareness. He chose to

run. (156)

In a single day, Shulgi ran

from Nippur to Ur, a distance of 100 miles (160.9 kilometres), in order to

officiate at the religious festivals in both cities, and then ran back from Ur

to Nippur; completing a run of 200 miles (321.8 kilometres) in one day. His

motivation in making the run is made clear in one of his inscriptions:

So that my name should be established for

distant days and never fall into oblivion, that it leave not the mouth of men,

That my praise be spread throughout the land,

That I be eulogized in all the lands,

I, the runner, rose in my strength, all set for

the course

From Nippur to Ur,

I resolved to traverse as if it were but a

distance of one `double-hour’

Like a lion that wearies not of its virility I

arose,

Put a girdle about my loins

Swung my arms like a dove feverishly fleeing a

snake,

Spread wide the knees like an Anzu bird with

eyes lifted toward the mountain. (Kramer, 286)

The run certainly accomplished

its objective, since Shulgi was associated with the event, and with great

stamina, in later chronicles. His courage and determination were also praised

because his run took place in the midst of a great storm. His inscription

continues:

On that day the storm howled, the tempest

swirled/The North Wind and the South Wind roared violently/Lighting devoured in

heaven alongside the seven winds/The deafening storm made the earth

tremble. (Kramer, 287)

So famous, in fact, did Shulgi

become for his run that he became a popular figure featured in erotic poetry

throughout Mesopotamia not long afterwards and was noted for his virility and

stamina as the lover the goddess Inanna.

Regarding the famous run,

Kriwaczek writes:

Could he really have done it? An earlier

generation of Assyriologists thought the achievement impossible, dismissing it

as fiction. More recent consideration, however, suggests otherwise. An article

in the Journal of Sport History quotes two relevant records: `During the first

forty-eight hours of the 1985 Sydney to Melbourne footrace, Greek ultra-marthoner Yannis Kouros completed 287

miles. This impressive distance was accomplished without pausing for sleep.’ In

the 1970’s a British athlete running on a track completed 100 miles in a time

of eleven hours and thirty-one minutes. There is no reason to believe that the Sumerians were any less athletically able. Theirs was,

after all, a far more physical world than is ours: speed, strength, and stamina

would have been much more important to them that they are to us. (157)

Shulgi’s run spread his fame

across the land, as he had hoped it would, and distinguished his reign

dramatically from his father’s.

While Ur-Nammu had presented

himself to his people as a father-figure guiding his people, Shulgi claimed the

status of a god. He made his run in the seventh year of his reign and, from

then on, was able to do as he pleased. It was customary in Mesopotamia to name

years after great feats accomplished by the king, usually military victories,

and the year of Shulgi’s run was thereafter known as 'The Year When the King

Made the Round Trip Between Ur and Nippur in One Day'.

The story of his run was

inscribed shortly after the event, and scribes were sent throughout the kingdom

to recite it in temples and present him to the people as an even greater king

than his father had been.

Later Reign and Controversy

His public relations campaign

was a great success. The Mesopotamian Chronicles describe Shulgi as

`divine’ and `the fast runner’ and tell how he generously provided food for the

cities, specifically the sacred city of Eridu. He was brother to the sun god Shamash and husband of the goddess

Inanna, according to hymns and songs. When he decided to expand his kingdom to

the north, the army followed him on campaign without question, and took the

region of Anshan (modern-day western Iran).

His continued policies of

taxation of the temples and temple complexes and the standardization of

weights, measure, time, and day throughout his kingdom had robbed the various

cities of their regional identities and, to a lesser degree, their economic

independence (the financial factor seems fairly negligible since many cities

continued to prosper economically after the fall of Ur), and yet there is no

evidence of domestic strife or reference to revolt in the records of his reign.

This peaceful and prosperous

version of Shulgi’s administration, however, has been challenged because first,

as already noted, the history comes from state-issued documents and, more

importantly, later writers claimed that Shulgi had purposefully falsified those

documents to present himself as the greatest of the kings of Mesopotamia.

The same chronicles which

present the king as divine also state that “Shulgi, the son of Ur-Nammu,

provided abundant food for Eridu, which is on the sea shore. …. Another passage

from the Chronicles claims that during Shulgi’s reign he “composed

untruthful stele, insolent writings, concerning the rites of purification for

the gods, and left them to posterity” (CM 27).

…. The Mesopotamian

Chronicles (also known as the Babylonian Chronicles) are a history of the

activities of the kings of Mesopotamia compiled by scribes at some point in the

1st millennium BCE from older sources. While scholars have long believed they

were composed at Babylon, there is reason to believe they were assembled at

different sites by different scribes under the direction of the Assyrian

Empire, probably by King Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE)

at Nineveh.

It is entirely possible, even

quite likely, that these later scribes, writing from a certain point of view and wishing to advance their own agenda,

edited or omitted certain details from the past in composing the chronicles,

but it is unlikely that they would have completely fabricated incidents and

passed them off as history. Most likely, they were drawing on the tradition of Mesopotamian Naru Literature which took

"factual" information and embellished upon it for effect in order to

transmit central cultural values - such as admiration for, and obedience to,

the king.

….

The Great Wall and the Death of Shulgi

Toward the end of his reign,

Sumer was becoming increasingly troubled by incursions from the nomadic tribe

known as the Amorites. Shulgi had a wall constructed 155 miles long (250

kilometres) along the eastern border of his kingdom to keep the Amorites out

but, as it was not anchored at either end, the invading nomads could simply

walk around it. The Elamites were also at the border but, during Shulgi’s reign

at least, were kept at bay by the army of Ur fortifying the wall.

After reigning for 46 years,

Shulgi died and was succeeded by his son Amar-Sin (r. 1981-1973 BCE) who

defeated the Elamites and strengthened the wall.

….

Shulgi’s death is as

controversial a topic as the records which describe his reign. Scholars

continue to repeat sentences such as “Shulgi may have died violently from an

assassin’s blow, along with his consorts Geme-Ninlila and Shulgi-Shimti”

(Bertman, 105) or “Shulgi may have died a violent death in a palace revolt” (Leick, 160) but it is uncertain whether this claim is valid.

The primary suspects alluded to by modern-day scholars are always Shulgi’s sons

but, in order for them to have assassinated their father and then assumed rule

after him, they would have needed some kind of support from the officials of

the court, their family, or by reading the discontent of the people and hoping

for popular support for a coup. ….

Conclusion

While the state records which

documented his reign have been challenged, the archaeological evidence from the

period supports their claims that Shulgi’s reign was indeed prosperous and that

the accomplishments he claimed for himself did happen, even if not exactly as

described.

Under his reign the roads were

improved, the kingdom expanded, the economy was strong, the inns were built, the calendar and time were

standardized, as were weights and measures, and literacy and the arts

flourished.

Whether he was guilty of

fabricating aspects of his life and reign is still debated, but there can be

little doubt that he was a man of enormous administrative and military talent,

imagination, determination, and personal charisma. One may question whether he

deserves the title he still holds as the greatest king of the Ur III Period

but, when one measures his accomplishments against his deficiencies, the former

outweigh the latter, and there were certainly no kings of the period who

followed him who were in any way his equal. ….

Another point to

be made is that the references to Ur Nammu as being the father of Shulgi tend

to occur in notoriously inaccurate, and very late documents, the The

Mesopotamian Chronicles (also known as the Babylonian

Chronicles), for instance.

Can

Hammurabi, too, be merged with his own supposed son, Samsuiluna?

The reason

why I wonder this is that Hammurabi defeated his long-time foe, Rim-Sin I of

Larsa, of whom we read in the Mari archive: “Ten to fifteen kings follow …

Rim-Sin, the man of Larsa …”, and Samsuiluna also defeated a Rim-Sim (so-called

II) of Larsa.

Marc Van de

Mieroop writes of these supposedly two Rim-Sin encounters:

P. 88:

“Hammurabi waited until Rim-Sin was an old man to initiate his swift conquest

of all his neighbours, including Lasa, which he conquered in 1763 [sic].”

P. 108:

“Only ten years after [Hammurabi’s] death, his son, Samsuiluna, faced a major

rebellion in the south led by a man calling himself Rim-Sin after Larsa’s last

ruler”.

In each

case, the defeated Rim-Sin soon apparently died:

In 1764 BC, Hammurabi turned against

Rim-Sin, who had refused to support Hammurabi in his war against Elam despite pledging his troops. Hammurabi, with troops from Mari, first attacked Mashkan-shapir on the northern edge of Rim-Sin's realm.

Hammurabi's forces quickly reached Larsa, and after a six-month siege the city

fell. Rim-Sin escaped the city but was soon found and taken prisoner and died

thereafter.[5]

Along

with many others at the time of Hammurabi's death, Rim-Sin II sees an

opportunity to lead a revolt against the rule of Samsu-iluna's Babylonian empire. The two fight for five years, with Rim-Sin

allied to Eshnunna, and most battles taking place on the Elam/Sumer

border before Rim-Sin is captured and executed.